Before the exhibition halls opened at the Africa Tech Festival and before the big-name tech sponsors took the stage, the conversation about AI in Africa had already turned philosophical at the 2025 Ministerial Forum.

Hover Gao, Huawei’s President for Sub-Saharan Africa, had just closed his keynote with a rallying cry for “national computing power” and “African foundational models.”

It set the mood for the morning, a mix of optimism and unease that now follows every AI discussion on the continent.

Then came the panel. The big question: What happens when AI meets human reality?

AI in Africa

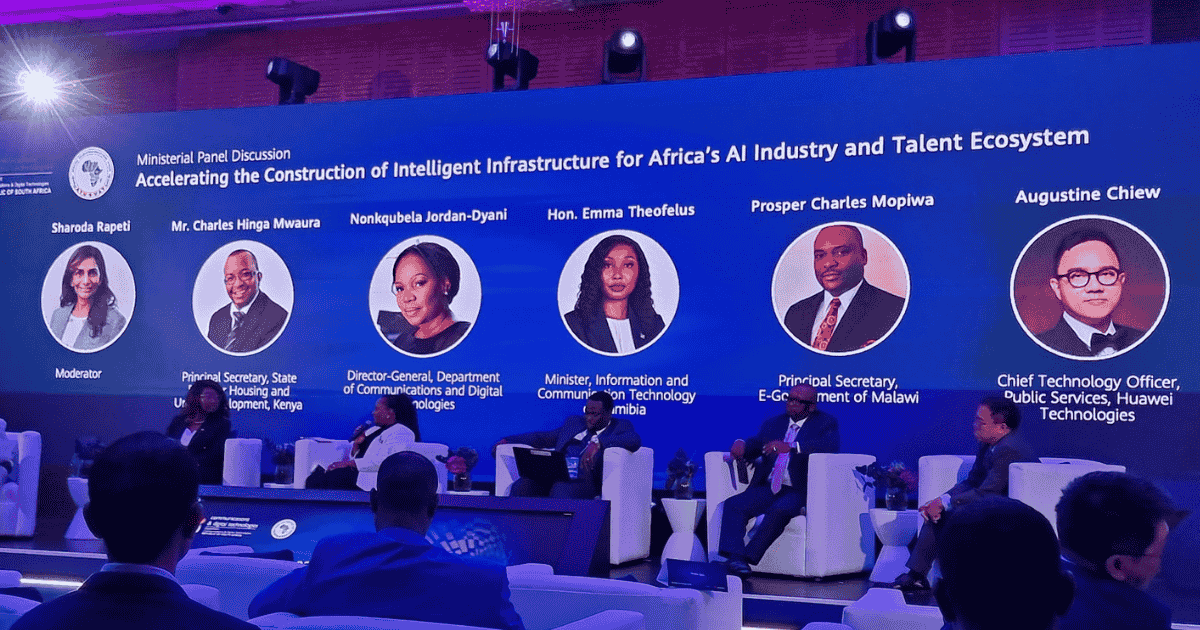

The session, moderated by Sharoda Rapeti, was titled “Accelerating the Construction of Intelligent Infrastructure for Africa’s AI Industry and Talent Ecosystem.”

It sounded clinical, but the tone shifted quickly once the ministers started speaking.

Emma Theofelus, Namibia’s Minister of Information and Communication Technology, opened with what she called “AI anxiety.”

She said the fear of artificial intelligence runs deeper than public opinion. “Before we even get to the general public, there is still a lot of work that needs to be done with policymakers and embracing AI”.

Theofelus described a growing tension: leaders who view AI as a threat to jobs and ordinary people who can’t tell the difference between deepfakes and real conversations.

“People are unable [to tell] AI-generated fake videos from the original thing,” she said. “That interaction is isolating some sectors of society and making them retreat because they can’t tell the real from the fake.”

Her argument was simple: AI mistrust is widening Africa’s digital divide. And fixing it starts with narrative.

“We can turn the tide by making people more aware of the potential gains that can come with AI,” she said.

ALSO READ: Solly Malatsi: ‘Wise choices’ will define the AI era, not machines

South Africa: policy on paper, skills still scarce

Nonkqubela Jordan-Dyani, Director-General at South Africa’s Department of Communications and Digital Technologies, picked up the thread with a policymaker’s realism.

South Africa has a draft AI policy almost ready for public comment. But the gap is capacity. “We may not have the adequate capacity in the public sector to run this,” she said.

She pointed to a deeper issue too: trust in data.

“We move across borders, so this particular issue of your data, you need to make sure the set of data that we have in South Africa, Namibia has got it, Nigeria has got it, Rwanda has got it,” she said.

Harmonising standards across the continent, she added, will be “key and partly linked to cybersecurity.”

Collaboration without duplication

The call for cooperation was echoed by Augustine Chiew of Huawei, who argued for smarter regional specialisation.

Instead of every country chasing the same AI industries, he suggested a model built on clusters, mirroring how Chinese provinces specialise.

“Would it make sense,” he asked, “to have a more holistic strategy? For example, this cluster of Southern African nations to develop AI capabilities around mining, transportation, governance?”

The idea: focus scarce budgets, share outcomes, and scale faster. It resonated with South Africa’s DG, who nodded to the need for “common standards, common laws, with regards to data governance”.

The ethics of ownership

When the conversation turned back to Theofelus, she pushed further into data sovereignty.

“We’re seeing a lot of our citizens’ data out there actually training models,” she said. “But there is no acknowledgement of the source of that data… and there is no compensation around those sources of data, and I think that’s an injustice.”

Her warning was measured but sharp: even open data must come with accountability.

“We have to find a model,” she said, “so there is no exclusion or authorisation of those data sets based on geography or demographic, but making sure that it works for all of us”.

Malawi: a strategy in the making

Prosper Charles Mopiwa, Principal Secretary for Malawi’s Ministry of Information Technology, struck a more pragmatic tone.

Connectivity, he said, has improved. Fibre now reaches most regional councils but the next frontier is human capital. “What we haven’t done yet is to align AI to these enablers for inclusive growth and innovation,” he explained.

Malawi is drafting its first AI strategy and plans to establish a national centre of excellence. “We need to put in place what we call quality institutions that can actually train or teach our citizens on what exactly AI in Africa entails,” he said.

He also extended an open invitation to collaborators. “I would like to open it up to the rest of the partners that are in this room. You can contact me directly or contact the ministers of ICT, we are at that stage where we need a lot of help.”

Kenya: data-driven housing and smart cities

If Malawi offered a plan, Charles Mwaura, Principal Secretary for Kenya’s State Department for Housing and Urban Development, provided the proof of concept.

Mwaura detailed how Kenya uses AI tools (drones, GIS mapping, and IoT sensors) to tackle urban challenges.

“We are putting up 200,000 units per year, and part of that is eradicating the slums,” he said. But before redevelopment, they use drones “to actually get the physical number of settlements that we need to work with so that we can compensate the people”.

Every new housing unit, he added, will come with high-speed fibre. “Connectivity is no longer a nice-to-have. It’s a new utility,” he said.

From consumers to producers

By the end, the conversation looped back to where Gao’s morning keynote had begun: Africa’s need for data sovereignty and regional strategy.

Jordan-Dyani closed with a call for innovation and inclusion. “The youth are at the centre of it,” she said. “We now need to create platforms where we actually profile those solutions… that again reaffirms the issues of digital sovereignty.”

The moderator summed it up neatly: Africa doesn’t lack ideas, just cohesion.

Some countries are moving faster than others but we all need to turn the tide around Africa being a consumer to Africa being a producer.